A Summertime ode to leisure

Summer is celebrated as a time of leisure in so many of our songs, such as Gershwin’s 1934 classic: “Summertime, and the livin’ is easy.”

Summer is celebrated as a time of leisure in so many of our songs, such as Gershwin’s 1934 classic: “Summertime, and the livin’ is easy.”

But slowing down, even in summer, is not easy for everyone. To all who identify with Martha, not Mary, in the oh-so-human Gospel scene of how two sisters respond to a visit by Jesus… this reflection is for you. Like Martha, many of us find ourselves amazed at how “busy we are about many things.” We tell ourselves that we would like things to slow down, but deep down we perhaps have a fear to really let that happen. The rhythm of our life centers on “doing” and “achieving.” Please permit me to introduce (or reintroduce) you to a few European thinkers who have some beautiful perspectives about the importance of authentic leisure – not only in the journey of a Christian, but in every human life.

The same year George Gershwin came out with “Summertime,” a young German philosopher named Josef Pieper wrote a work on the virtue of fortitude in which he criticized the Nazi regime, warning of an attack that “declares war on the primacy of the Spirit itself.” Twenty years later, having witnessed the tragic effects of Nazism, Pieper published one of the most important books of the century, Leisure: The Basis of Culture. It is a short read that many people have found life-changing.

Pieper provides the antidote to the epidemic of workaholism in the modern world which Max Weber also observed in 1905’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism: “One does not only work in order to live, but one lives for the sake of one’s work, and if there is no more work to do one suffers or goes to sleep.” This brings to mind Blaise Pascal’s famous insight that “all of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Pieper describes how in ancient Greece, the view of work and leisure was much different. Work was viewed by philosophers like Aristotle as a means to an end… namely, the goal of creating time for authentic leisure. Merriam-Webster defines leisure as “freedom provided by the cessation of activities.”

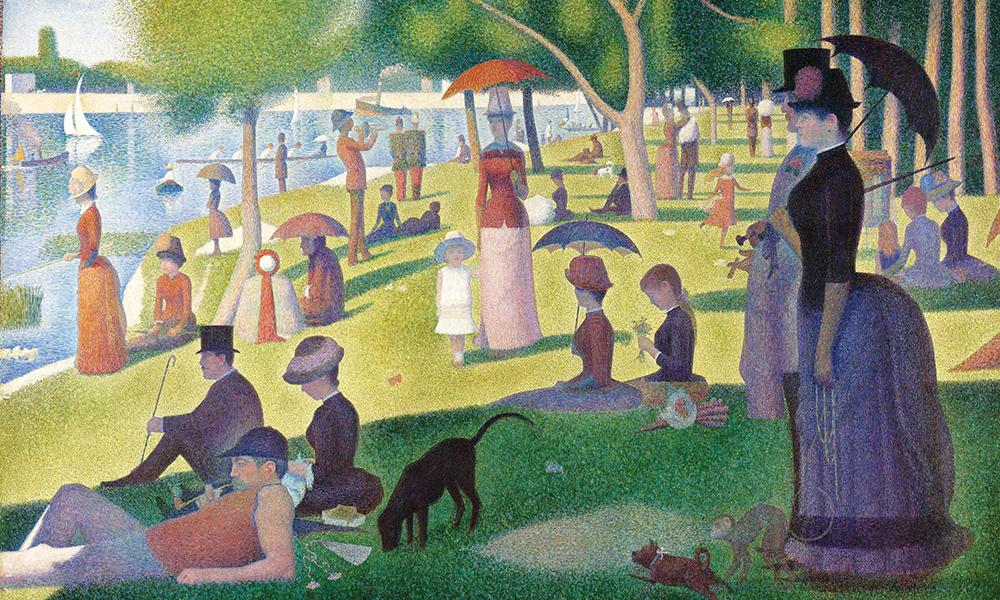

For Pieper, leisure indicates time to freely enjoy and contemplate all that is good, true and beautiful in the world. Clouds that look like turtles, the kindness of another, the luminous look of glee in our children’s eyes as they play tag, the wisdom of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130, or the transcendent finale of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” There is a good reason that the humanities are often called “the liberal arts.” They liberate us by setting our minds free and our spirits soaring.

We often hear that recreation is supposed to “re-create” us. But for those of us addicted to “doing,” that can be a challenge.

I’m reminded of a Jesuit priest suffering from burnout because he was always on the go. In We Neurotics, Father Bernard Basset, SJ, shares that he was becoming desperate when someone suggested he visit a nearby nun. “She’s a little cranky, but she can help you.” At his first meeting, she sized him up and said something along these lines: “I want you to pick a nice day each week, go out into a field, lie down and look up for an hour.

If you do that for the next two months, I will agree to be your spiritual director.” She was trying to help the priest to live a more receptive, affective life rather than just an effective life.

An affective life is more heart-centered, experiencing God’s gifts in a spirit of thanksgiving; the effective life can feel more like being a cog in the societal machine of productivity. Pieper notes: “The inmost significance of the exaggerated value which is set upon hard work appears to be this: man seems to mistrust everything that is effortless; he can only enjoy, with a good conscience, what he has acquired with toil and trouble; he refused to have anything as a gift.”

St. John Paul II offered a beautiful meditation on how original sin is connected to the inability of our first parents to simply receive God’s gifts. Instead of receiving the gifts with open hands and open hearts, they fell into the temptation of grasping.

Concentration camp survivor and Catholic psychologist Conrad Baars also offers important insights about the value of leading an affective life in a workaholic world. . He realized that many of his patients in the Netherlands were leading lives of frenetic action – always trying to do more and achieve more. He came to understand that many of these people never received affirmation of their fundamental goodness growing up, so they spent their lives trying to fill that void by gaining recognition for what they were able to achieve. When he would speak about this in front of high-powered doctors and lawyers, some of them would get teary-eyed because they realized his diagnosis was right on target.

In response, Dr. Baars and his colleague, Dr. Anna Terruwe, created a therapeutic approach called “affirmation therapy.” It is significant that when Mother Teresa read Baars’ book, Born Only Once: The Miracle of Affirmation, she wrote to him to say that he had captured the essence of her religious order’s ministry— namely, to affirm everyone in their fundamental goodness as children of God.

As Christians, we are blessed to have a heavenly Mother who not only lovingly affirms us in our fundamental goodness as only a mother can, but who can also help us live more contemplative, receptive and affective lives. She is the New Eve who, with open hands and heart, is fully receptive to the Lord, reversing the grasp of the first Eve. It is for good reason that the Apostles – rugged men of action, including fishermen and a Zealot – spent nine days in Mary’s presence before Pentecost. Who better to prepare the hearts of these men to receive the Holy Spirit than the one who, with her spirituality of receptivity, “kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Lk 2:19). And who better to teach us how to slow down and allow ourselves to be impacted by all the good that God gives us with a receptive and thankful heart.

As a young Father Josef Ratzinger pointed out in Introduction to Christianity: “From the point of view of the Christian faith, man comes in the profoundest sense to himself not through what he does but through what he receives. … For his ‘salvation’ man is meant to rely on receiving. The primacy of receiving is not intended to condemn man to passivity; it doesn’t mean that man can now sit idle … On the contrary, it alone makes it possible to do things of this world in a spirit of responsibility, yet at the same time in an uncramped, cheerful, free way, and to put them at the service of redemptive love.”

Dr. Dan Osborn is the Diocesan Theologian and Coordinator of Permanent Diaconate Formation & Ministry for the Diocese of Saginaw.